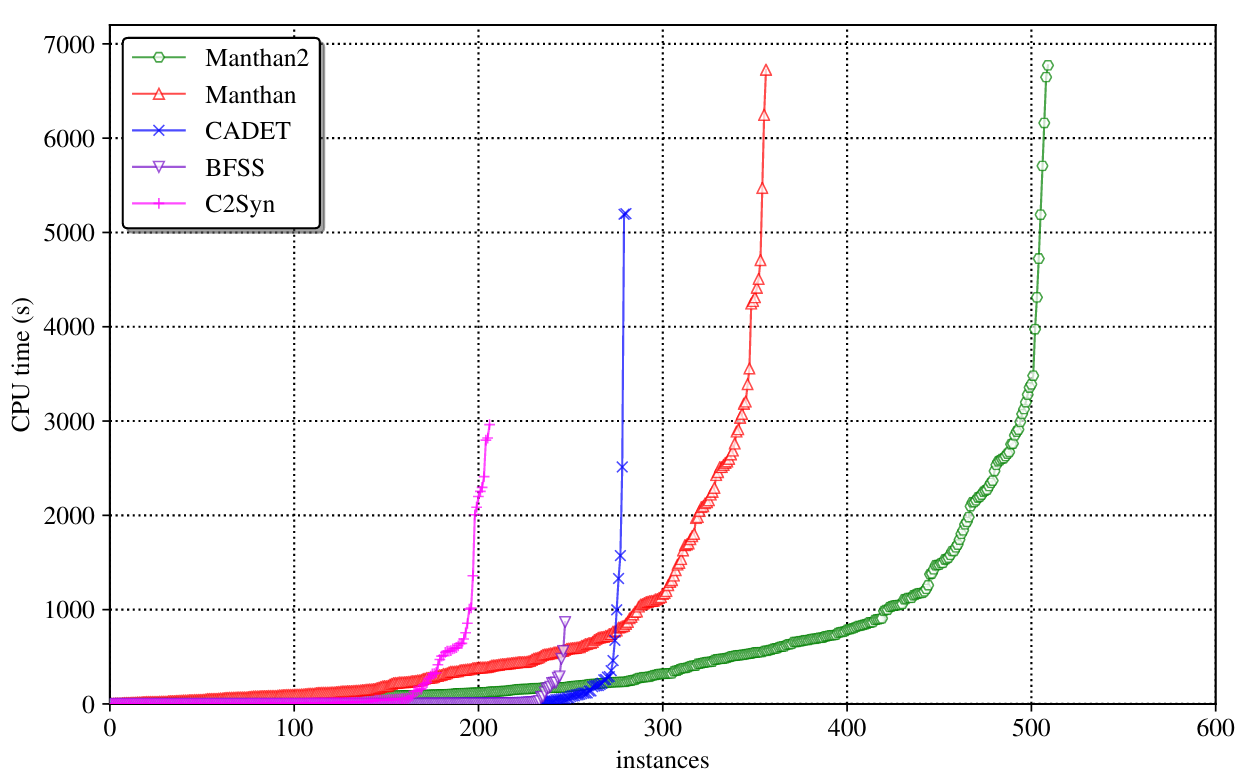

This post is just a bit of a recap of what we have developed over the years as part of our toolset of SAT solvers, counters, and samplers. Many of these tools depend on each other, and have taken greatly from other tools, papers, and ideas. These dependencies are too long to list here, but the list is long, probably starting somewhere around the Greek period, and goes all the way to recent work such as SharpSAT-td or B+E. My personal work stretches back to the beginning of CryptoMiniSat in 2009, and the last addition to our list is Pepin.

Overview

Firstly when I say “we” I loosely refer to the work of my colleagues and myself, often but not always part of the research group lead by Prof Kuldeep Meel. Secondly, almost all these tools depend on CryptoMiniSat, a SAT solver that I have been writing since around 2009. This is because most of these tools use DIMACS CNF as the input format and/or make use of a SAT solver, and CryptoMiniSat is excellent at reading, transforming , and solving CNFs. Thirdly, many of these tools have python interface, some connected to PySAT. Finally, all these tools are maintained by me personally, and all have a static Linux executable as part of their release, but many have a MacOS binary, and some even a Windows binary. All of them build with open source toolchains using open source libraries, and all of them are either MIT licensed or GPL licensed. There are no stale issues in their respective GitHub repositories, and most of them are fuzzed.

CryptoMiniSat

CryptoMiniSat (research paper) our SAT solver that can solve and pre- and inprocess CNFs. It is currently approx 30k+ lines of code, with a large amount of codebase dedicated to CNF transformations, which are also called “inprocessing” steps. These transformations are accessible to the outside via an API that many of the other tools take advantage of. CryptoMiniSat used to be a state-of-the-art SAT solver, and while it’s not too shabby even now, it hasn’t had the chance to shine at a SAT competition since 2020, when it came 3rd place. It’s hard to keep SAT solver competitive, there are many aspects to such an endeavor, but mostly it’s energy and time, some of which I have lately redirected into other projects, see below. Nevertheless, it’s a cornerstone of many of our tools, and e.g. large portions of ApproxMC and Arjun are in fact implemented in CryptoMiniSat, so that improvement in one tool can benefit all other tools.

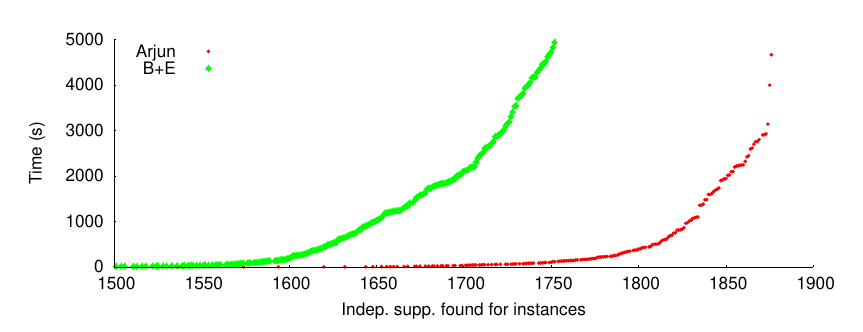

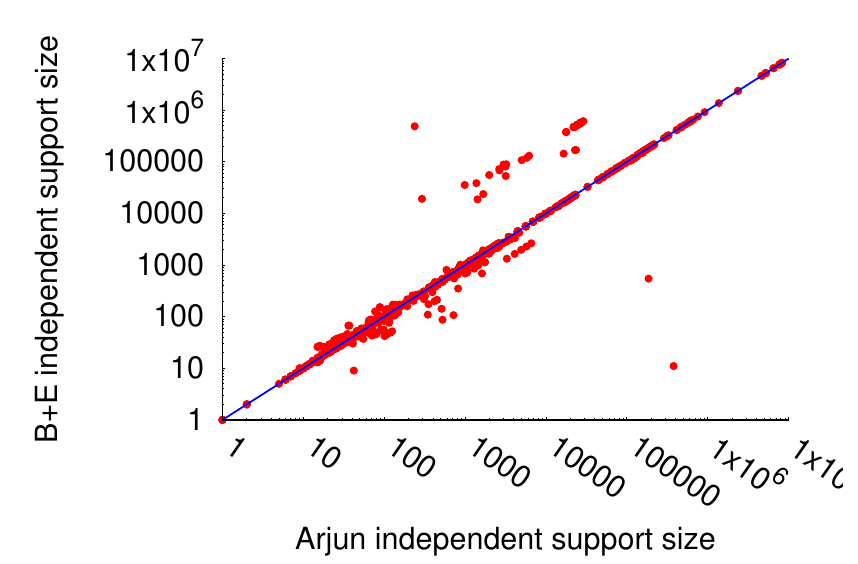

Arjun

Arjun (research paper) is our tool to make CNFs easier to count with ApproxMC, our approximate counter. Arjun takes a CNF with or without a projection set, and computes a small projection set for it. What this means is that if say the question was: “How many solutions does this CNF has if we only count solutions to be distinct over variables v4, v5, and v6?”, Arjun can compute that in fact it’s sufficient to e.g. compute the solutions over variables v4 and v5, and that will be the same as the solutions over v4, v5, and v6. This can make a huge difference for large CNFs where e.g. the original projection set can be 100k variables, but Arjun can compute a projection set sometimes as small as a few hundred. Hence, Arjun is used as a preprocessor for our model counters ApproxMC and GANAK.

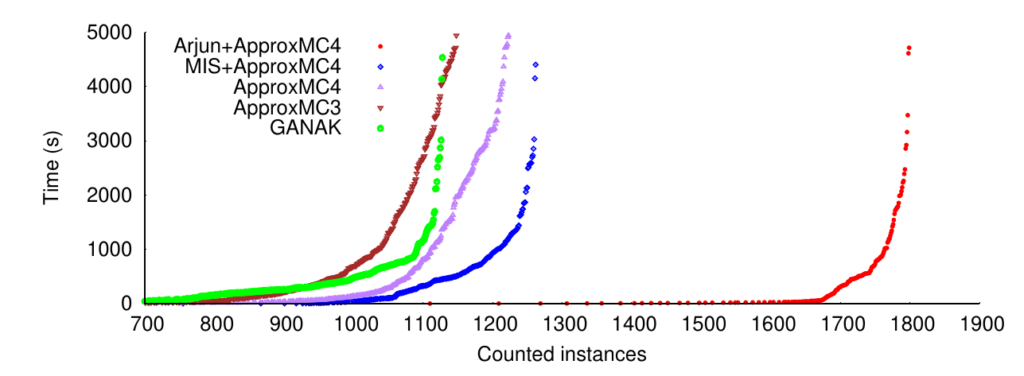

ApproxMC

ApproxMC (research paper) is our probabilistically approximate model counter for CNFs. This means that when e.g. ApproxMC gives a result, it gives it in a form of “The model count is between 0.9*M and 1.1*M, with a probability of 99%, and with a probability of 1%, it can be any value”. Which is very often enough for most cases of counting, and is much easier to compute than an exact count. It counts by basically halfing the solution space K times and then counts the remaining number of solutions. Then, the count is estimated to be 2^(how many times we halved)*(how many solutions remained). This halfing is done using XOR constraints, which CryptoMiniSat is very efficient at. In fact, no other state-of-the-art SAT solver can currently perform XOR reasoning other than CryptoMiniSat.

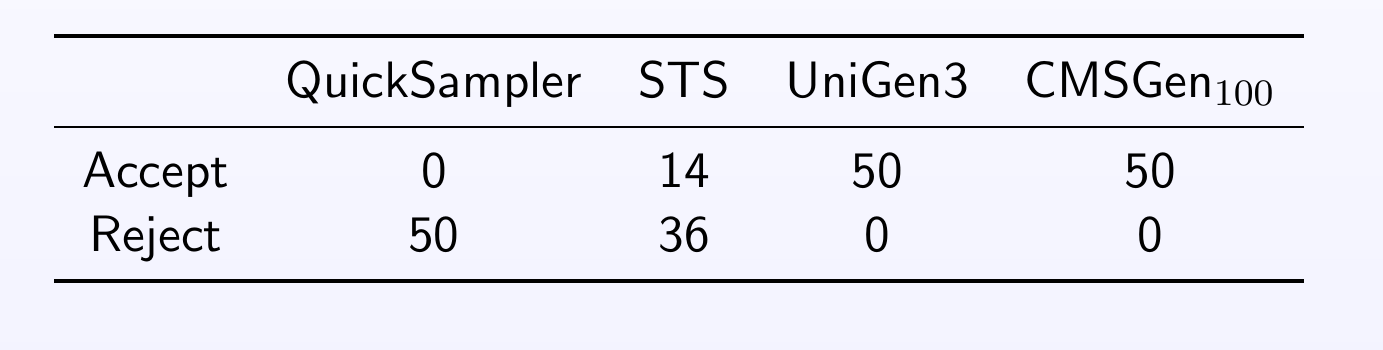

UniGen

UniGen (research paper) is an approximate probabilistic uniform sample generator for CNFs. Basically, it generates samples that are probabilistically approximately uniform. This can be hepful for example if you want to generate test cases for a problem, and you need the samples to be almost uniform. It uses ApproxMC to first count and then the same idea as ApproxMC to sample: add as many XORs as needed to half the solution space, and then take K random elements from the remaining (small) set of solutions. These will be the samples returned. Notice that UniGen depends on ApproxMC for counting, Arjun for projection minimization, and CryptoMiniSat for the heavy-lifting of solution/UNSAT finding.

GANAK

GANAK (research paper) is our probabilistic exact model counter. In other words, it returns a solution such as “This CNF has 847365 solutions, with a probability of 99.99%, and with 0.01% probability, any other value”. GANAK is based on SharpSAT and some parts of SharpSAT-td and GPMC. In its currently released form, it is in its infancy, and while usable, it needs e.g. Arjun to be ran on the CNF before, and while competitive, its ease-of-use could be improved. Vast improvements are in the works, though, and hopefully things will be better for the next Model Counting Competition.

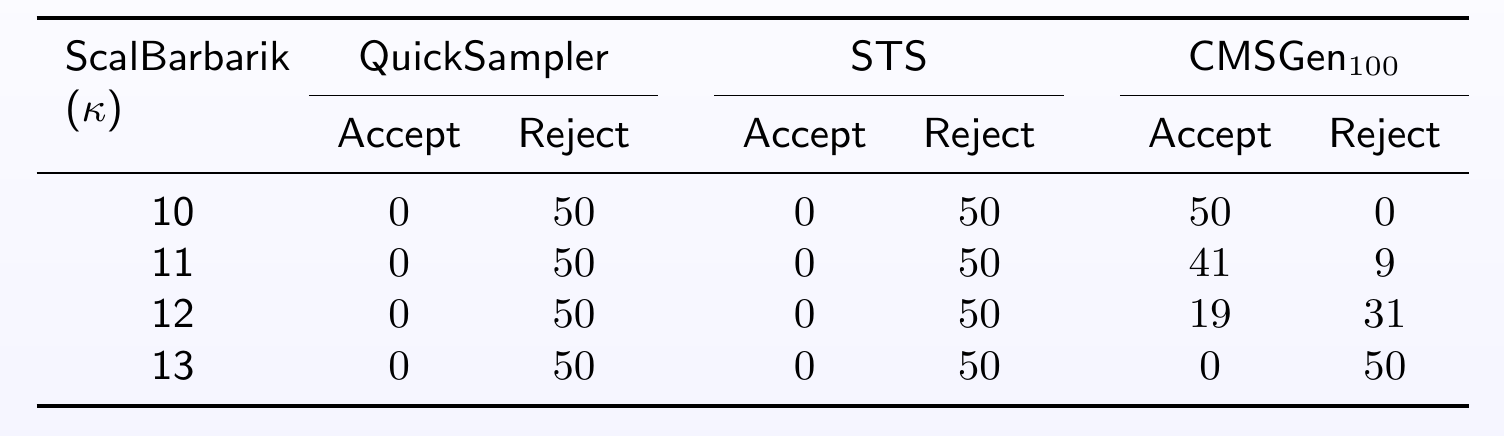

CMSGen

CMSGen (research paper) is our fast, weighted, uniform-like sampler, which means it tries to give uniform samples the best it can, but it provides no guarantees for its correctness. While it provides no guarantees, it is surprisingly good at generating uniform samples. While these samples cannot be trusted in scenarios where the samples must be uniform, they are very effective in scenarios where a less-than-uniform sample will only degrade the performance of a system. For example, they are great at refining machine learning models, where the samples are taken uniformly at random from the area of input where the ML model performs poorly, to further train (i.e. refine) the model on inputs where it is performing poorly. Here, if the sample is not uniform, it will only slow down the learning, but not make it incorrect. However, generating provably uniform samples in such scenarios may be prohibitively expensive. CMSGen is derived from CryptoMiniSat, but does not import it as a library.

Bosphorus

Bosphorus (research paper) is our ANF solver, where ANF stands for Algebraic Normal Form. It’s a format used widely in cryptography to describe constraints over a finite field via multivariate polynomials over a the field of GF(2). Essentially, it’s equations such as “a XOR b XOR (b AND c) XOR true = false” where a,b,c are booleans. These allow some problems to be expressed in a very compact way and solving them can often be tantamount to breaking a cryptographic primitive such as a symmetric cipher. Bosphorus takes such a set of polynomials as input and either tries to simplify them via a set of inprocessing steps and SAT solving, and/or tries to solve them via translation to a SAT problem. It can output an equivalent CNF, too, that can e.g. be counted via GANAK, which will give the count of solutions to the original ANF. In this sense, Bosphorus is a bridge from ANF into our set of CNF tools above, allowing cryptographers to make use of the wide array of tools we have developed for solving, counting, and sampling CNFs.

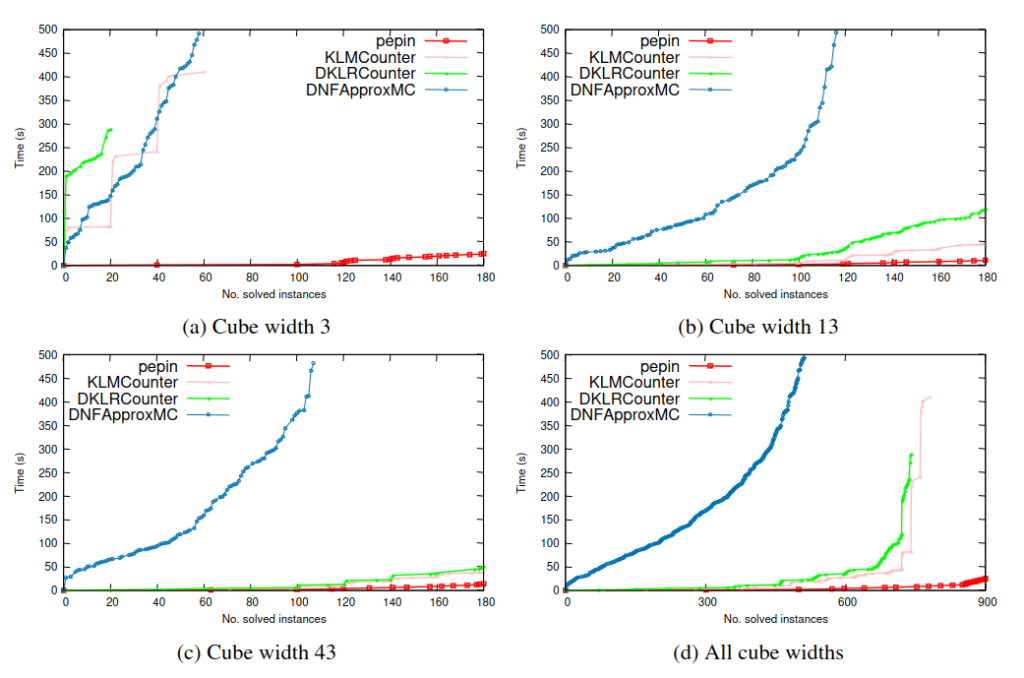

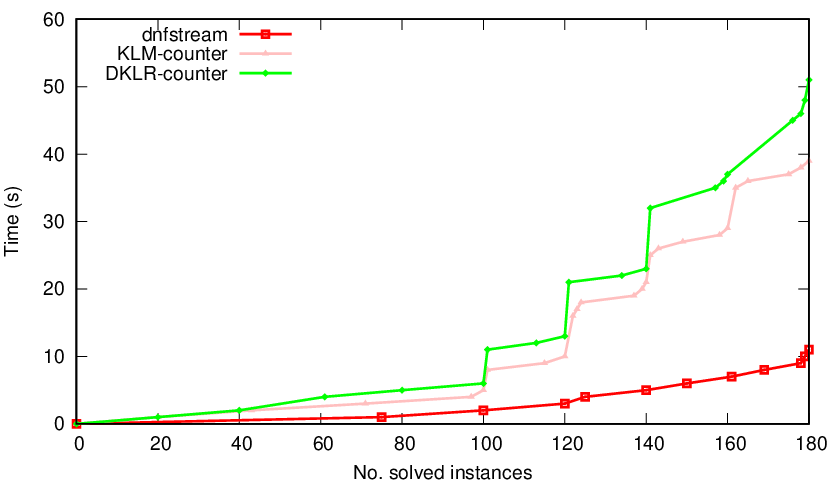

Pepin

Pepin (research paper) is our probabilistically approximate DNF counter. DNF is basically the reverse of CNF — it’s trivial to ascertain if there is a solution, but it’s very hard to know if all solutions are present. However, it is actually extremely fast to probabilistically approximate how many solutions a DNF has. Pepin does exactly that. It’s one of the very few tools we have that doesn’t depend on CryptoMiniSat, as it deals with DNFs, and not CNFs. It basically blows all other such approximate counters out of the water, and of course its speed is basically incomparable to that of exact counters. If you need to count a DNF formula, and you don’t need an exact result, Pepin is a great tool of choice.

Conclusions

My personal philosophy has been that if a tool is not easily accessible (e.g. having to email the authors) and has no support, it essentially doesn’t exist. Hence, I try my best to keep the tools I feel responsible for accessible and well-supported. In fact, this runs so deep, that e.g. CryptoMiniSat uses the symmetry breaking tool BreakID, and so I made that tool into a robust library, which is now being packaged by Fedora, because it’s needed by CryptoMiniSat. In other words, I am pulling other people’s tools into the “maintained and supported” list of projects that I work with, because I want to make use of them (e.g. BreakID now builds on Linux, MacOS, and Windows). I did the same with e.g. the Louvain Community library, which had a few oddities/issues I wanted to fix.

Another oddity of mine is that I try my best to make our tools make sense to the user, work as intended, give meaningful (error) messages, and good help pages. For example, none of the tools I develop call subprocesses that make it hard to stop a computation, and none use a random number seed that can lead to reproducibility issues. While I am aware that working tools are sometimes less respected than a highly cited research paper, and so in some sense I am investing my time in a slightly suboptimal way, I still feel obliged to make sure the tax money spent on my academic salary gives something tangible back to the people who pay for it.